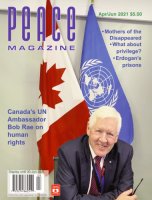

Ambassador Bob Rae on Human Rights

On March 11, Project Save the World interviewed Bob Rae, Canada’s Ambassador to the United Nations. Three activists joined Metta in questioning him about three ongoing human rights crises. Charles Burton, a diplomat who lived many years in China, asked him about Canada’s work at the UN on behalf of the Uyghurs. Paul Copeland, a retired human rights lawyer with long experience in Myanmar, asked about the plight of the Rohingya and the current coup in that country. Calixto Avila, an activist in Belgium with the human rights group PROVEA, asked about the crisis in his homeland, Venezuela.

By Bob Rae; Charles Burton; Paul Copeland; Calixto Avila; Metta Spencer (moderator) | 2021-04-01 12:00:00

METTA SPENCER: Hi, I’m Metta Spencer. And hello, Ambassador Rae.

AMBASSADOR BOB RAE: Hello, Metta. Nice to be with you.

SPENCER: It’s a treat for us. Let’s start this conversation with Charles Burton, who is concerned about the situation of the Uyghurs in China.

CHARLES BURTON: It’s a great honor to speak with our ambassador to the United Nations. Yesterday on the CBC, General Roméo Dallaire suggested that the Canadian government is showing a lack of statesmanship with regard to the Uyghur genocide. To my understanding, China ratified the Convention on Genocide in 1983. But, like so many of the conventions that China ratifies, it refuses to accept any kind of review by the International Court of Justice. There are also genocide provisions in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, but China is not signatory to the Rome Statute. My question for you, as Canadian ambassador to the UN, is, do you see any way forward for the UN to effectively stop the genocide by the government of China against the Uyghurs and Turkic Muslims living in the northwest? In the past Canada has expounded the Responsibility to Protect doctrine but I’m not seeing any movement on the part of Canada in the UN, specifically to try to end the horrors that the Uyghurs are suffering.

RAE: Well, thanks, Charles, it’s good to see you again, and to talk to everybody. First I just want to put a couple of things on the table. One of my first interventions in the General Assembly involved a response from the government of China to a statement that somebody else had made. In it they went after Canada for its positions on human rights. The principal objection of the government of China was that these are China’s internal affairs—nobody else’s business. This is not a new argument. It’s held by many other countries at the UN, including Russia, Syria, and the debates we’ve had around those issues. In my response to the ambassador, I said, Look, whether it’s the Convention on Torture, or the Geneva Convention, or the Convention on Genocide, or the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice itself, member states like China have, in fact accepted that there is no such thing as absolute sovereignty. There is no sovereign protection from the review of the world and global institutions like the International Court of Justice on human rights. And in all of the cases that we’re going to be discussing today: in Myanmar and Venezuela, the response from the regimes is the same. And the response from Canada is also the same—that there’s a thing called international law. There are institutions to enforce international law and now is the time to be making that very clear.

My second point is, it’s not so much what Canada does on its own as what Canada does with others. Whether it’s the interventions in Myanmar, or what’s happening in Venezuela, or what’s happening in China, Canada cannot have much impact on its own. We can have far more impact to the extent we persuade others to come with us, or frankly, to which others persuade us to come with them. I respect General Dallaire very well. We served together in Parliament; he was a member of the Senate, I was a member of the House of Commons. I worked with him closely on issues around child soldiers at the United Nations. And I’m here simply to say: There are steps that have to be taken that the Government of Canada is taking before any final decision can be made about how we’re going to be engaging with the International Court of Justice or other institutions.

Charles, you mentioned the International Criminal Court. The problem we have there is that 70 countries in the world have not signed onto the Rome Statute. China is one, Myanmar is another. Venezuela—as you go down the list, you see here we have a problem. Governments have not accepted the jurisdiction of the criminal court. And the way the Rome Statute is structured limits the ability of the criminal court to take jurisdiction. On the Genocide Convention, on the International Court of Justice, we’re already in court. Canada is supporting The Gambia and has already filed, together with The Netherlands, a clear indication that we’re going to be participating in that hearing. We’ve learned from the Rohingya situation (and I had something to do with the approaches that Canada has taken) that it takes a lot of time to document what is happening that go beyond newspaper reports and other accounts. It has to be based on information that can then become evidence. It’s going to take time, but when you’re saying, “Is there something that can be done?” the answer’s yes. There are steps that can be taken, but they have to be systematic, well organized, and presented well. But there are a number of countries at the UN—for example, 39 countries last year signed a statement that took clear issue with the way China was handling the issues of the Uyghurs, Tibet, and Hong Kong. China took great offense and made their own statement. But to suggest that we’re sitting on our hands is really not accurate. We are actually addressing it. But when you’re looking at something as complex as a genocide case at the International Court of Justice, you don’t just leap into it. We need to gather the evidence and do the work. That’s exactly what Minister Garneau has said he wants to do. And that’s what we’re doing.

BURTON: China took a reservation on the provisions of the Genocide Convention with regard to the International Court of Justice, so they don’t accept the jurisdiction. Certainly in terms of whether or not genocide is taking place, the report released March 9 by the Newlines Institute and the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights, of which I know you are a supporter and member, is pretty convincing and includes an endorsement by Yves Fortier, the former Canadian ambassador to the UN and three former Liberal cabinet ministers, Irwin Cotler, Alan Rock, and Lloyd Axworthy.

The idea that China denies that there is genocide doesn’t really stand up. You did refer to the 39 countries that supported the idea, but China was able to rally a larger number of countries that opposed the idea. So when one looks at a situation where China’s a member of the P-5, is able to mobilize more countries than we can with regard to this issue, will not accept the jurisdiction of either the ICC or the International Court of Justice, is it possible for us to actually implement anything like the Responsibility to Protect in the context of the UN as it stands? If Canada does rally together countries to engage in some common action, China is not likely to end the genocide. If Canada does get a condemnation through a legitimate basis, it could be similar to China’s response to the International Court of Arbitration in The Hague’s determination that China is in gross violation of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, where China rejected an over-400-page decision as a worthless piece of paper. Is the UN able to function as an effective body in enforcing the Genocide Convention, which was in fact, the founding convention of the institution? Is there any hope?

RAE: Of course there is. it’s just not easy, that’s all! I mean, Charles, all you’re describing is how difficult it is. You’re saying China is a superpower. China doesn’t like other people commenting on what they do. China behaves in an arbitrary way. We know that. And is it tough? Yeah, of course, it’s tough. The first year we put out the statement, we had 24 people signing on; now we have 39. This is not about giving up. This is about understanding that these things are tough. The RTP doctrine is the same. RTP is a very well-thought-out and positive way of saying that countries have a responsibility to protect their own people, that the neighbourhood around has a responsibility to make sure that it happens, and that the international community has to come in and do something. Okay, you’ve got a nice building. You’ve created it, it’s painted, it’s nice. How do you actually do it? And the answer is: with great difficulty. China won’t accept that they’re doing something wrong. They vociferously reject it. The neighbourhood around China is not about to do much. And globally, we’re facing a challenge that China’s very powerful. But does that say something about the UN? It says that the UN is made up of a number of countries, many of which are very authoritarian, not remotely democratic, and have no intention of changing their ways. That’s not the fault of the UN. You don’t blame the Air Canada Centre when the Maple Leafs lose. It’s the team. It’s the countries that make up the UN that are the problem. And the countries that make up the UN are a mixed bunch. This is the swimming pool I’m in every day, and it’s full of sharks. Swimming in it is difficult, sometimes dangerous—but not as dangerous for us diplomats as for the people who are living in Xinjiang. That’s where we have to focus. There are terrible human rights abuses taking place in China today and we have to work every possible angle we can to get them to stop.

BURTON: What would be the next steps in the UN? The international community is moving toward some likely unified action in terms of sanctioning the Chinese officials who are complicit in the genocide—some of whom have assets in Canada. But where do you see it going? And how long before you see movement on this file?

RAE: There now are very active discussions among a number of governments about what more can be done, and the steps that need to be taken together. The election of President Biden has changed the dynamic. We are actively talking to the United States and to a number of other governments about steps that they are looking at. There’s a consensus that it’s what we do together that matters. It’s not one country saying, I’m going to do this and other countries saying I won’t do that. We don’t assume that the international institutions are going to do it on their own.

We’re not precluded from taking our own actions, but our own actions will be much stronger when they’re done in concert with others. And as we speak, those are discussions are underway, on China, Russia, Myanmar, Venezuela. We’re asking how we can be more effective in protecting human rights.

BURTON: Well, on behalf of my Uyghur friends and here in Canada, I really pray that we can move as expeditiously as possible to save those people. You know, I’ve seen documents that suggests that the Chinese government has a 40-year program to eradicate the Uyghur “tumor.” It’s already underway so it’s urgent to make this a priority for our Canadian foreign policy. And thank you.

RAE: It is a priority that we all have to keep working at.

SPENCER: Okay. Now, let’s shift to another part of Asia. Paul Copeland sends me messages about Myanmar every day now. You probably are on his list too.

RAE: I get the same messages, Metta. Don’t worry. (We laugh.) They’re good messages.

COPELAND: I would like to give a little history of the Rohingya in Burma, and then pose a question to Bob. I’ve been involved in Burma stuff since I first visited the country in 1988. I was back four more times over the years. I’ve worked a lot with Burmese people here and internationally on democracy issues.

In 1820, the British took over Western Burma and brought in the Rohingya to farm there. When the country gained independence in 1947 they were granted citizenship. The military took away their citizenship in 1982. In 2013 some fighting went on with the Rohingya and the military, and 100,000 of them ended up in an internally displaced persons camp in Burma. In 2017 there were some very serious attacks done by the military. They claimed that they’d been started by the Rohingya, although I don’t believe that. And 700,000 of them fled to Bangladesh to join people that had already gone there. Bob Rae did a report for the Government of Canada on the situation of the Rohingyas.

Gambia has brought an application in the International Court of Justice, which is ongoing. The first of February of this year, the military did a coup, which took over the government. The elections in November had been won by the National League for Democracy, led by Aung San Suu Kyi. There’s 700,000 in IDP camps in Bangladesh. Some of them have been transported to an island that, to me, sounds pretty horrible. Burma is under a military dictatorship again, and their military is killing people and locking up lawyers there. So, Mr. Rae, please give me your thoughts on what might happen that could be productive for the Rohingya.

RAE: Thank you, Paul. First, thank you for your work over many years. You and I’ve been talking about Burma and Myanmar ever since you’ve you first went. I did some work with the Forum of Federations where we were acting as an NGO on governance issues. The Forum is still going strong. That was my initial contact with Myanmar. I visited in the earlier part of 20 years ago, and then again in 2015. Then the prime minister asked me to go back and engage in some work on the Rohingyas, as you’ve said. Again, it’s a huge challenge for us in Myanmar’s failure to make a successful transition to democracy. Remember how we talked about how there’s a transition, and I said we don’t know yet whether there’s going to be a transition. What we know is that the military fashioned a Constitution in 2008 that protected their power perpetually.

Eventually, Aung San Suu Kyi said, “Okay, I can live with this, I need to get back and join the democratic struggle.” She decided to come back from house arrest and lead her political party in the next available election, after reaching an agreement with the generals as to how that would be done. But from my observation in 2017-18, when I was able to speak with her, I was very disappointed. The Rohingya issue for her was not a big deal. It was a particular part of the country, where she felt there were security issues, the army had acted appropriately, and I needed to get educated on what was going on.

I then held meetings with the army and two meetings with the Rohingya and went into the IDP camp where people had been since 2012. And the camp in Cox’s Bazar, where people have been since 2017. I saw a humanitarian tragedy and an act of brutal discrimination and indeed genocide, in my opinion, on the part of the Tatmadaw against the Rohingya. And then appallingly, frankly, Aung San Suu Kyi defended the situation in front of the International Court of Justice, where I was also attending as an observer. That caused the reaction to her from the rest of the world that we know only too well.

But the long and short of it now is that the military has shown once again (they didn’t need to persuade me) that this is a brutal, frankly, criminal enterprise that has run the country for 60 years in total disrespect of human rights. Over 60 people have now been killed on the street. Like you, Paul, I’m getting daily reports as to how bad it is. What’s required is as much joint action as possible from a number of countries who are willing to take a leadership role in opposition to the coup and support the incredible courage and resiliency of the people of Myanmar. It’s extraordinary what’s happening. People who have no access to weapons, the civilian population, has a general strike going on. We have a withdrawal from work of millions of people. And a military regime that’s responding with brutal force.

You can ask the same question as Charles asked: What are you doing? And the answer is, we’re carrying out a process of sanctions, but we’re also carrying out a whole engagement with other countries to say what further steps we can take.

But here’s the dilemma. After 1960, we thought we were, quote, isolating Burma. But we weren’t. What we were doing was driving them into the arms of the Chinese, who were only too happy to say, we’re here for you! And a number of other countries invested quite substantially in Myanmar, particularly Asian countries, and saw them through the period of sanctions and everything else to the emergence of the Aung San Suu Kyi government in 2015. As a result of geography and economics and the actual situation on the ground, Canada does not have much leverage in Myanmar. People say, why can’t Canada get the government to do this? We have no tools to do that. We don’t have the people, the money, the influence, acting alone. Acting together, we have some, but not enough to overthrow a government. The only people who can really change the government in Myanmar are the people of Myanmar, with as much support as we can provide them. That struggle is underway right now. I don’t believe the coup will permanently end the emergence of democracy. There’s just too much going on on the ground. And there’s a deep commitment on the part of the people of Myanmar to their future. But again, we have to act together. Is it having great effect? Not as much as any of us would like, but we’ll keep working at it.

SPENCER: More, Paul?

COPELAND: No. Just after the coup I was totally frustrated and lost hope for the Rohingya. There’s very little hope for anything meaningful happening in Myanmar in the near future. I’m still a director of the Law Society. They’re trying to get a human rights monitoring group to put out a statement because there’s some serious repression going on of lawyers in Burma.

RAE: Totally! They’ve arrested some of the leading human rights lawyers in the country. They prevented Aung San Suu Kyi’s lawyer from seeing her. They’ve put up a bunch of bogus charges against her. Lots of things that are happening are absolutely criminal. Some say there’s nothing we can do. But you say, Well, yeah, you can actually describe it. You can say this is what’s happening. I was in the General Assembly ten days ago when the Myanmar ambassador spoke. I’d met him, talked to him before. I wasn’t totally shocked by what he said because I had a sense of what he was going to do. But he showed tremendous courage and there are a lot of other Myanmar diplomats around the world who not going to support what the regime is doing. This is causing way more reaction than the military expected. They thought they could get away with it and that people would believe them when they said, “Don’t worry, we’ll have another election in a year. We’re just here to kind of deal with a problem with the last election.” There was no significant problem with the last election. They lost it. Aung San Suu Kyi won it. That’s what they didn’t like about it. But this is why I say the coup is a coup, not a constitutional move by the army. It’s a coup, and we need to describe it for what it is.

SPENCER: My concern is that in this thing that’s going on with the government now, we had become disillusioned with Aung San Suu Kyi, but now she’s the victim that we have to protect—her party and so on. And it looks as if the concern about the Rohingya has to be put on hold while the other issues are being fought. Am I mistaken in seeing that these two issues are almost perceived as contradictory?

RAE: No, I’m not sure I agree with you but I don’t know whether you’re mistaken. I always start every conversation thinking maybe I’m mistaken. But my sense is that something interesting is happening. Remember that, in addition to the resistance among the population living in large urban centres in Myanmar, the Bamar people who live in Yangon and Mandalay and the other major cities, there has been since 1947-48 a fighting force in every other region of the country, the Chin, the Kachin, the Karenni, the Shan state. If you think of Myanmar as a horseshoe, you’ve got the part of the horseshoe that goes right around the country in mountainous areas. And those people are not putting up with this. They have been engaged in military action against the government of Myanmar for many years and they haven’t gone away. The peace process that Aung San Suu Kyi took charge of in 2015 has not done much.

And so those people have come together. During the Rohingya crisis, there was slowly but surely a change in the thinking of those groups around the Rohingya. They began to realize that the challenge facing Rohingya was also facing them, and they needed to find common ground. I think that’s taken hold now in the democratic movement in Myanmar. Aung San Suu Kyi won the last election. She should be released from prison and take the office that she won. But I think she will inherit a democratic movement different than the one that she thought she was leading when she went into prison this time.

I have not given up on the ability of the Myanmar political system to see the protection of the Rohingya as something they need to do as well. Maybe that’s too optimistic but I don’t think it’s impossible. That’s what we should be aiming at. Canada certainly is not dropping its support for the Rohingya or for dealing with the challenge that they face.

SPENCER: Well, that’s the nicest thing you’ve said all day! I had the contrary opinion. My assumption was that most of the people who had been themselves victims in these struggles, these ethnic wars and who were immigrants or refugees in Canada, were very supportive of the oppression of the Rohingya. And if you’re saying that they’re coming around, seeing the similarity between their own predicament and that of the Rohingya and learning something from this experience, well, that’s good news.

RAE: I’m not pretending it’s simple. As Paul laid it out in his brilliant capsule history of modern Burma, the issue around the Rohingya is really an issue of identity. It is about: Are you one of us, or are you part of somewhere else? And when I think of the Rohingya, I think of the Roma in Europe, where many say the Roma are not part of us. They’re foreigners, outsiders. The Rohingya are a people whose history in relationship to Myanmar dates back at least 200 years. Some of them are Muslims living in Rakhine state who have been there for hundreds of years. To say that they have no connection to Myanmar is just not true. These people have to be included. But in the British Empire in Asia, a lot of boundaries and borders were taken down, a lot of freedom of movement took place. And when national movements of liberation in India and Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Burma happened, there was a drive to re-establish borders and boundaries and to insist that these people are not part of us.

These issues are happening throughout Asia. It’s a little present that the British Empire left behind. It’s Afghanistan, Pakistan—the border lines that were created by the British. It’s a function of Empire. It’s not just the British Empire; the same thing with the French Empire. We’re living with the consequences of that, and in the new world national groups, ethnic groups say, “the British did this,” or “the French did this,” or some other country did this to us. That’s not who we think who we are. So, it’s complicated.

SPENCER: Well, thank you. Now let’s go to Belgium and meet Mr. Avila. I have not had a conversation with him yet about his position. Perhaps the people he’s representing are more favourable toward Canada’s position than the two people who have been sort of scolding you for not doing more. Let’s see what happens.

RAE: I don’t consider Mr. Burton or Mr. Copeland to be scolding me. It’s fine. I’m a big boy, I can take it. Don’t worry about it. (We laugh.)

SPENCER: Well, I farmed that task out to them so I wouldn’t have to scold you myself. So there you go. Okay, Calixto Avila, you’re in Belgium. Please brief us on your situation. I know that you’re concerned about the conflict over who’s the real government in Venezuela.

CALIXTO AVILA: Yes, I thank you for the opportunity. We are a human rights organization so we are focused on the humanitarian and human rights situation in Venezuela. Of course, we really appreciate the role played by Canada in trying to reach a solution to the crisis in Venezuela. Canada has played a key role in the Lima group, which is one of the best actors in trying to reach a political solution. Also, Canada played a vital role in beginning the preliminary examination at the office of the prosecutor in the ICC. And there is a preliminary examination in Venezuela that’s focused on crimes committed there since 2017. Canada has played this role, despite having no embassy open in Caracas. But despite all this activity of Canada, the Maduro government is more and more closed. In December, we had the last elections on the new National Assembly, which is considered as not free and there is not full respect of national standards—even in terms of constitutional standards. So, we are facing a humanitarian crisis with more than five million migrants in the region. This is a human rights crisis but all the actions of the international community seem unable to change the dynamics. The government of Maduro is more and more consolidated in power and civil society is more and more persecuted. What other actions can be done by the international community if the situation is being more and more established? There is no change in the short term. Canada has been playing a role as an independent actor, but also playing a role in terms of international collectivities, with other countries in the region and in the United Nations. But what can we expect to do, if the situation is not changing despite the important activity of the international community? That will be my question.

RAE: I appreciate your question and I appreciate your perspective, because I think it’s important. There is of course a debate in Canada, as elsewhere, on the nature of the Chavez-Maduro governments. The response from a number of countries—the United States, Canada, a number of other governments around the world, within the region, within Latin America, South America. Some are countries that are part of the Lima group, some are countries that are not part of the Lima group. It is complicated, but it’s not that complicated. Canadian policy has consistently been committed to democracy, freedom of speech, and diversity of opinion. I don’t want to get into history except to say that the facts that you’ve described are ones that I think are very clear. There is a humanitarian crisis. There are five million Venezuelan citizens who have felt the need to leave the country in recent years. Before, over many years, there was a significant exodus of Venezuelans, but principally people who were better off and who chose to leave the country and move to the United States or elsewhere. That was the first big exodus. But the exodus we’re seeing now is much bigger in numbers. Five million working people, working families, poor people who’ve lost everything, who have nothing and who have crossed the border over into Colombia and Brazil and other parts of Latin America. We have a huge presence in Peru and Ecuador. We have a big Venezuelan group that’s moving up through Central America.

It’s important for Canadians to know that there’s a significance to our engagement on this as a country, because of our membership in the OAS. We are a country of the Americas. Many Canadians think of ourselves as connecting more to Europe or Asia, but not necessarily to Latin America and the Americas. But we are part of the Americas and, having joined the OAS and taken an interest in governance throughout the Americas, we’ve become implicated in this discussion. A number of countries, including our own, hoped that the congressional leadership led by Mr. Guaidó would actually be successful in a democratic encounter with the Maduro administration. That didn’t happen. It shows that if you are in control of the apparatus of the state, that’s a lot. Opposition forces that may seem influential are not as influential as they think. There’s a comparison between Aung San Suu Kyi and Mr. Guaidó in their relationship to state power, because state power in Myanmar and Venezuela was in the hands of authoritarian forces supported by military. The civilian opposition couldn’t overcome that, so we’re now living with the consequences.

So, what’s happening? Well, everyone is reassessing. The Lima group is regrouping. We have meetings in New York and in the OAS in Washington. Discussions are going on in different places. Canada is involved with the refugee situation in Colombia, where we profoundly support the government of Colombia for what they’ve done. They’ve indicated that 1.7 million refugees in their own country will be allowed to stay, work, and get education, which is a huge decision. Same thing is happening in a number of neighbouring countries. Peru, Ecuador, and others are being very positive. We are assisting in that process and helping to fundraise for the UNHCR. The Minister of International development of Canada is leading efforts to raise awareness and funds for the international agencies in the situation.

This is not intended to get into too big an argument, but any notion that there’s something romantic or progressive about the Maduro regime is mistaken. There are some people who say it’s a socialist government that socialists should be supporting. I would say, if you have an ounce of democracy in your bones, you can’t support the Maduro regime because there’s nothing remotely democratic about it. It’s an oppressive government. There’s evidence of torture and extraordinary abuse of power. The unilateral, arbitrary authoritarian actions by the government are completely incompatible with democracy and we need to come to grips with it.

We also need to come to grips with the current situation and our government is assessing that. What is the best and most effective way to respond? We’re not backing off on our view that there are issues of accountability and impunity that need to be looked at. That’s why we’ve been looking at international legal steps that can be taken. But we also have to see what the Europeans are prepared to do. What are the Americans prepared to do? How can we be a constructive player? We are very involved in those discussions and that’s important for your supporters to know.

SPENCER: May I ask your views about sanctions? Because there’s a debate among Venezuelans as to whether that’s a good thing or not.

RAE: My view is that we should be very careful in sanctions policy with any country, to make sure that their impact is not falling primarily on the least well-off. And the other aspect of sanctions is, are they effective? Are they actually doing what we think they should be doing? Or are they making the situation worse? Are they strengthening the hold that the government has over the people? That’s a factual issue to be assessed on a factual basis. One thing we’ve developed is this concept (Charles referred to it with respect to China) of Magnitsky sanctions—sanctions that are targeted directly at individuals who, we have reason to believe, have some responsibility for a particular abuse of human rights. Those sanctions can be effective.

SPENCER: And morally more defensible than when it’s uncertain who’s going to be hurt most.

RAE: But it’s both a moral question and a practical question. The moral question is, is this the right thing for us to do? Is this sustainable? But the second question is, is it actually being effective? But I think that’s something which governments have an obligation to assess all the time. Our government is looking at it, with respect to all of our sanctions: Where is the burden falling? And is this effective? That’s being reviewed all the time, as it should be.

SPENCER: Right. We have a couple of minutes and I’d like to invite anybody who has a burning question or comment.

AVILA: Maybe something more about the sanctions. We support the request of the High Commissioner, Madam Bachelet. She’s asking everyone to lift the sectoral sanctions. We support this demand because the effects of the sanctions inside the country are worsening the situation of the population. But we have to distinguish between these sectoral sanctions and individual sanctions for human rights violations. We support the latter kind, because we consider them useful to send a strong message to those who are responsible for these actions.

Another thing: Maduro is using the sanctions to diminish his own responsibility for corruption. Venezuela has much corruption and the government is saying no, the sanctions are responsible for the humanitarian crisis, not the years and years of corruption of the income from petrol revenues. So, I think it’s very important to recognize this difference and to know how such a regime can use the sanctions as an excuse to claim that they are not responsible—to blame another actor, not the government itself.

SPENCER: Can I ask whether the Lima group is reassessing the question of sanctions? The public doesn’t know what you guys are talking about, you know.

RAE: What we’re talking about is, how can we assist in what is an appalling human rights situation inside Venezuela? Secretary Blinken has already said that he’s going to be there looking at sanctions as it impacts on humanitarian situations in a number of countries. I think that will include Venezuela. A number of countries are doing what we’re doing because we’ve got to make sure that what we’re doing is effective. That has to be assessed on an ongoing basis. The Secretary General of the UN asked everybody to look at them because of COVID-19. It’s having a major impact in Latin America, including Venezuela and Colombia.

SPENCER: Indeed. Anybody else?

BURTON: Well, I’d like to thank Mr. Rae for giving a sincere and honest account to us ordinary Canadians, taking an hour of his time. I’ve been a long-time admirer of Mr. Rae, and I think he’s an excellent representative of Canada in the UN.

RAE: Oh, thank you, Charles, I appreciate it. The government has encouraged me to engage with Canadians on issues of foreign policy and human rights. They’ve given me this license and I try to engage with representatives of civil society and student groups, all of the opportunities that are made available through the miracle of Zoom. About the only positive thing I can think of about the technologies that have arisen during COVID is that they make it much easier for us to communicate with one another directly and encourage a dialogue between officials and citizens.

SPENCER: I think every one of us celebrated when we heard that you were going to be the UN ambassador for our country. It’s a good choice. I’m really happy that you’re there and I’m very, very grateful to you for spending time with us and clarifying all these issues that need so much more work.

RAE: Nice to talk to you. Thanks, Metta. That was great.

SPENCER: Everybody take care of yourselves. Bye.

The above interview is also available on video (YouTube or Facebook); podcast (tosavetheworld.ca/podcasts or projectsavetheworld.libsyn.com); and transcript (peacemagazine.org/archive/v37n2p16.htm). See tosavetheworld.ca for more details.